During my time working in Product Management, I have encountered a couple of different definitions of what a Product Manager should do. Probably the best place to start as I begin to blog about the topic, is to provide my own definition. It is worth mentioning that I do not consider this to be the “correct” definition of Product Management. Indeed I believe there is no such thing as a “correct” definition as the implementation of the role should vary to some degree from person to person based on their capabilities and style. This is mine.

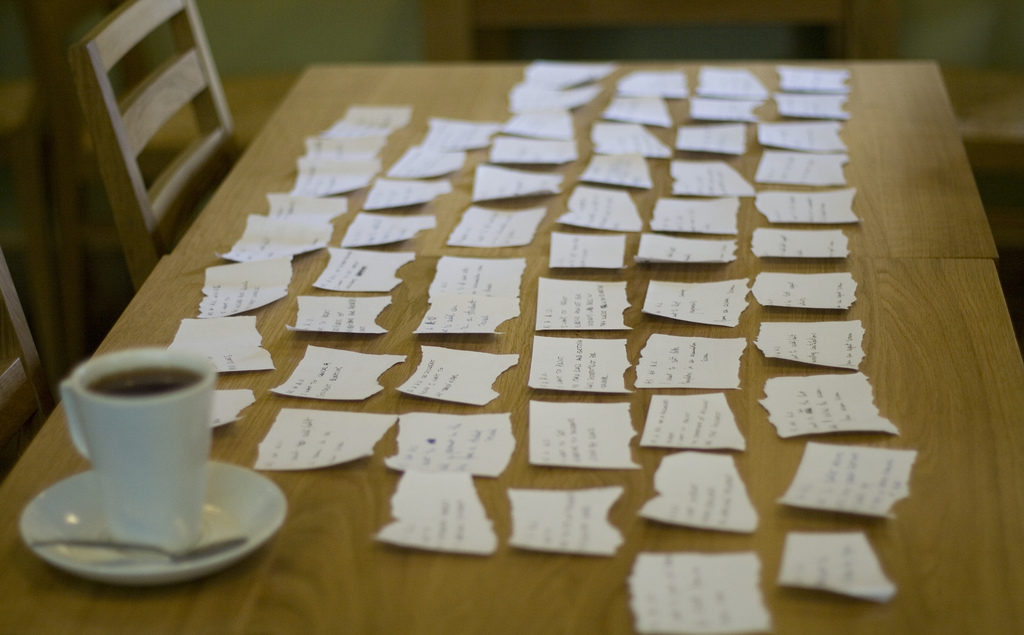

User stories in Oxford by Jacopo Romei (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Know your Market

Strive to be the expert in the space your product occupies. There is at least one goal (probably more) behind every use (and every purchase) of your application, understand the goal, be it a solution to a problem, a feeling, a desire, whatever… Know the people behind those goals, speak to them (really do this, don’t just read a report you downloaded).

You are unlikely the first to try and meet that goal. Look beyond just your direct competitors and consider anyone your users might consider in helping them meet their goal. Know those competitors and their products as well as you know your own.

Finally, understand the technicalities of your industry and the problem domain. If you are building software, then you should know a thing or two about programming, if your product tackles personal finance then you should know a thing or two about banking. This is not to say that you should try and do everybody’s job, but make sure you are not the guy that always needs everything explained to them (that is not so say you shouldn’t ask questions. Actually, ask lots of questions).

Make your product successful

A Product Manager should strive to make their product successful. Most Product Managers will operate in the context of an organisation that has set a goal driving the existence of their product. This goal might be part of the organisation’s longer term strategy, or it might be a shorter term, tactical goal. Meeting this goal is realistically one of the first measures of success.

Further defining success and measuring against that definition is the next step for a Product Manager and will generally involve exploring one or more business models. If revenue (direct or indirect) is the driving force then projections and financial models should tie in to concrete quantifiable goals to help ensure success. Revenue might not always be the driving force though: influence and impact could be two other goals for a product. Sometimes products are not successful. Catching failure (and learning from it) is another vital function of the Product Manager, even if it sometimes involves rowing against the current.

The final measurement of a products success will come from its users. The ultimate goal would be to build a product loved by its users. Sometimes love is too much to ask for, many a car enthusiast will claim to love their car, but one would be hard pressed to find anyone that loves their motor oil. Customer satisfaction, retention rate and recommendation rate are valid measurements across contexts.

Help the right people do a great job

You know your market and you have defined success, your next task will probably involve a whole bunch of other people helping turn vision into reality. As a Product Manager, you manage nobody and although you are probably expected to be a polyglot, you very likely know a lot less about everyone’s job than they do. Striking the right balance between providing a direction to the product creation process and staying out of the way is therefore important.

One of the first teams you will probably collaborate with is your design team. With training in user research, user experience design and interaction design, your designers are the experts that will help you understand the goals and possible solutions for your target user.

In parallel, you will start working at verifying targets and numbers, working closely with teams such as Finance, Sales and Business Intelligence. Get their guidance and their buy in for your plans, remember, they are the numbers experts.

Collaboration with Engineering is stereotypically strained and left for as late as possible. It doesn’t need to be this way. Even if you have a technical background, include Engineering as early as possible (even when talking to users). In this relationship, you are either a resource or an overhead. Avoid being the latter by always bringing something valuable to the table: your knowledge of the user and the problem domain, your influence in the business to help remove impediments, and if you have nothing else to bring, bring pizza.

Fill in the gaps

Found something not covered above, not covered by your team, that needs to be done to make the product successful? Yep that is your responsibility. Find somebody to do it or if you can, do it yourself. This might sometimes involve being very hands on filling a gap in the organisation, helping an overworked team and sometimes it involves bringing food when teams work through the weekends or doing the boring paperwork. If you identified the gap then you are probably the best person to fill it. Just don’t overwork yourself, there are after all only 24 hours in a day.